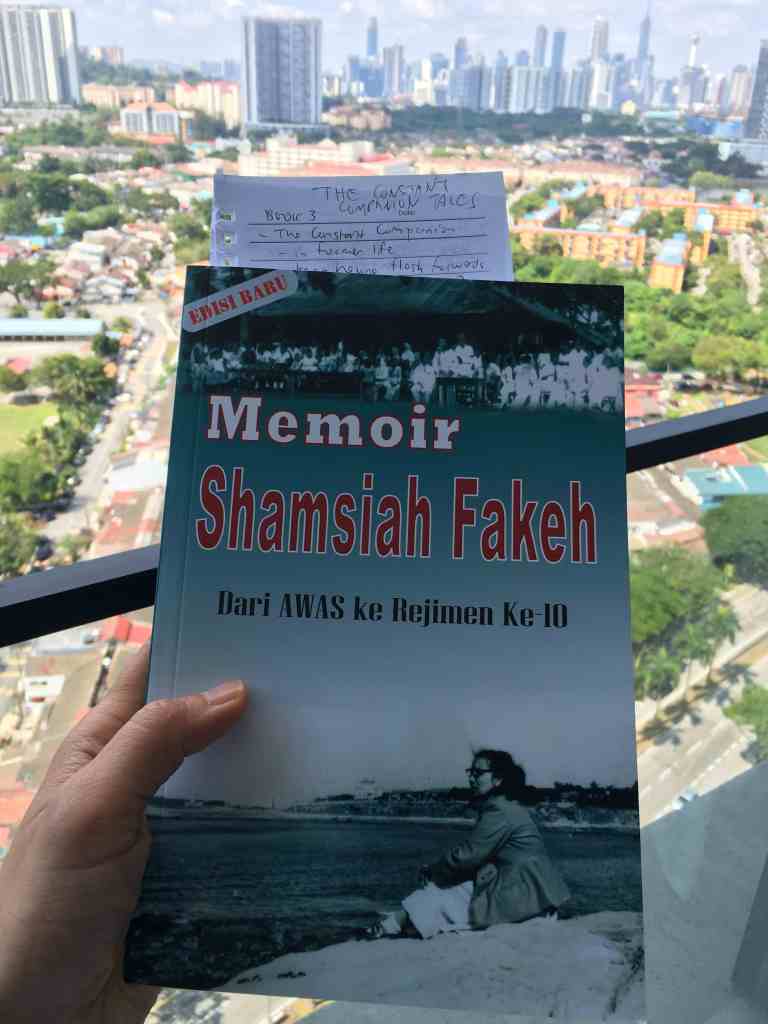

Shamsiah Fakeh’s memoir of her time with the 10th Regiment of the Malayan Communist Party complements the other half of the story I first learned as a child, when my father served with the 1st Royal Malay Regiment. Both form the narrative of my country’s independence.

I’m reading Shamsiah Fakeh’s memoir of her time with the Malayan Communist Party (MCP)’s 10th Regiment. My father served in the 1st Royal Malay Regiment (1 RAMD) at the height of the 2nd Emergency (1960s-1987). As a child, I remember him speaking of Shamsiah in a wistful manner, never disparaging, of the bafflement and regret he felt for a lady his mother’s age who spent her time battling her own people in the jungle.

In Memoir Shamsiah Fakeh, Fakeh describes the painful moments that led to her deciding to fight for my country’s independence in a path less travelled by many. Poverty, the useless husbands, feminism and a sense of justice. A story or propaganda of her that spooked me as a child was of her throwing her two-month old son into the river to stop the pursuing army from hearing his cries. In this memoir, Fakeh clarifies that the baby was killed by her own comrades. They took him off her, promising to have the baby adopted. Three years later, she discovered they tossed him into the river. She accepted it, a victim of circumstances. I don’t accept it.

A story that spooked me as a child was of her throwing her two-month old son into the river to stop the pursuing army from hearing his cries. In this memoir, she clarifies that the baby was killed by her own comrades.

She describes in detail the layout of her encampment, and how the insurgents lived in the jungle. It’s like her memoir completes the other half of the information I have of their lives – a life I saw through photographs that my father brought home of the hastily abandoned campsites. As part of his study of the then enemy. Her people leave in a haste; my father’s people follow soon after. And what we have to join the dots are this memoir and my father’s photographs.

She explains, and we follow with empathy, of the events leading up to the banishment of the Malayan Communist Party at midnight, 20 June 1948. But she doesn’t mention the tragic murders on 16 June 1948 that led to the Malayan Emergency declared. You can read about it in my fantasy horror books or by going to my wiki (“State of Emergency”).

Perhaps one day our Warrior Day at Putrajaya can be commemorated by all sides? Men and women fell on both sides to pave the way for us.

It’s sad to read the part where she recounts her first encounter with 30 MCP insurgents in the middle of World War 2. They came to her house whilst she was alone, asking to buy rice, later sugar cane, for food. They came by to ask for water. They didn’t harm her, and that made an impression on Fakeh, who then knew and cared little of the political dynamics of World War 2.

In 2018, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier laid a wreath at the Cenotaph in London, UK, on Remembrance Day on behalf of the German people in an historic act of reconciliation. My sister and I were there. We saw a long line of Germans queuing up to pay their respects for the first time ever. They spoke German at the event, unheard of before 2018.

Perhaps one day our Warrior Day at Putrajaya can be commemorated by all sides? Men and women fell on both sides to pave the way for us. Perhaps we can dig deeper to find that acceptance and forgiveness.

Memoir Shamsiah Fakeh is available at Gerakbudaya. Lead image: 13-year old Shamsiah Fakeh with her family.