My horror stories are about people trying to get out of situations. The conundrum lies in the choices they make: how to quit being a warrior without leaving any more dead bodies behind.

The making of a Type A personality

Not long ago, I was provided an evaluation of my personality based on the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). It was based on a quick online survey filled out during a hectic week, so I’d say the evaluation has caveats attached.

It reminded me, however, of a similar MBTI assessment carried out a long time ago when our triathlon coaches wanted to determine that the squad members were of the desired Type A personality. They wanted to make sure we could finish the race.

Triathlon, for those unfortunate enough to fall into it as a pastime, is a scary experience. It has all the right components of horror. You fear drowning? The first stage is swimming. You don’t know if your heart will pack it in before you cross the finishing line – or worse, lose control of your bowel movements and crap your pants? There’s the running stage. Are you fearful of speed, crashes and negotiating sharp corners? Cycling, the last stage, provides those thrills.

Everyone panics and falls apart at some point when faced with trauma. But if planned well, the self-inflicted trauma won’t happen during the race. Ideally, it should occur after and preferably elsewhere. I suspect that was why the emphasis was on finding candidates who could be trained to be a Type A personality. The thinking behind it was that we follow the race plan faithfully, as trained, and then cope with the aftermath as intended.

Everyone panics and falls apart at some point when faced with trauma. But if planned well, the self-inflicted trauma won’t happen during the race. Ideally, it should occur after and preferably elsewhere.

Natural born warriors

Triathlon is a form of habitus – you use it to tacitly signal your achievement to your peers. You opt in to be a weekend warrior.

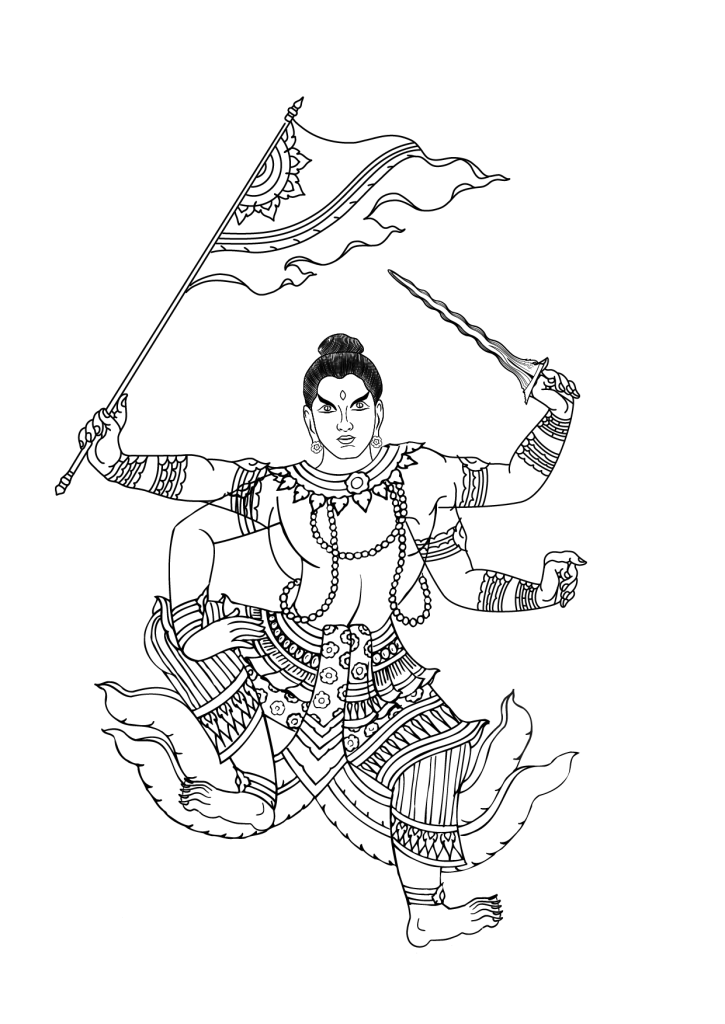

My horror stories, however, are about those who can’t easily opt out from what they’re born into. The characters of the Raden family are based on the kesatriya or the warrior caste. Some time ago at anthropology school, I read a paper by G. M. Carstairs, Daru and Bhang: Cultural Factors in the Choice of Intoxicant (1954), published in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. It was for medical anthropology. Carstairs explains that the brahmins, top of the varna or social class, aren’t permitted to eat meat or drink alcohol. Their choice of intoxicant is therefore the bhang – marijuana by-product made of leaves and seeds. The kesatriya, tasked with safeguarding their people, are permitted to eat meat and drink alcohol.

Because of this huge responsibility to protect the citizens, kings and princes come from the kesatriya caste. Their ‘royal’ status provides them with a duty to protect. It isn’t a privilege. If they’re called in to sacrifice their lives for their people, they can’t easily opt out. Despite their status, however, they’re still below the brahmins in the social pecking order. At least, this was the structure in some parts of India and in the Indianised kingdoms of Southeast Asia centuries ago. As many moved towards Buddhism and Islam, the class structure of the ruling class remains.

How not to be a warrior

The Tiger-Man and His Constant Companion is partly set in the pre-World War 2 period when the Raden family – of Javanese aristocracy – begin their new life in British Malaya as commoners. Islamised for some time and emasculated by Dutch imperialism, the young Raden cousins consciously opt out of their class. Although their ancestors were kesatriya, when our story begins, they’re farmers by choice.

Their problem, however, is the war. Weapon-less and pushed to a corner, the young men are faced with two choices: submit to enemies’ sword or revert to the warrior-caste mode. Their ghostly servant, the constant companion – the metaphor of this gruesome and overwhelming responsibility – hasn’t tasted human blood for a long time. With the war, it receives permission to kill again. The Radens know there’s no turning back from this point onwards. And that’s how the story rolls.

Enter the Tiger-Man

The Tiger-Man and His Constant Companion was the hardest of the series to write but to my surprise, it resonates strongly with my readers. One person actually said she likes it although it’s by far the darkest of the three series.

A compelling character that I’m continuing to expand on for Part Four is the soldier boy Yamashiro. He has a very imaginative way of opting out of his predicament. I won’t tell you what it is but suffice it to say that both he and the were-tiger are in the same boat. They’re both prescribed a life of violence but not by choice.

As soon as I finished writing The Tiger-Man, I knew that the story of Yamashiro and the were-tiger won’t end there. A plot is developing in my head.

As soon as I finished writing The Tiger-Man, I knew that the story of Yamashiro and the were-tiger won’t end there. A plot is developing in my head.

My inspiration for Yamashiro’s character is a prince who famously snuck out in the middle of the night to leave his burdensome life behind. What Siddharta Gautama did wasn’t without serious repercussions. His action threatened the delicate balance that had held together his warrior caste for hundreds of years. But by opting out to become an arhat, he spared his wife of a certain fate faced by widowed women: death on the funeral pyre. And by doing so he showed many princes that there is a way out, if only they leave their ego behind.

It is this tension that I try to explore. The Raden family tries to fit into the modern world that is genteel, civilised, with past conflicts glossed over. But this is a vulnerable façade. The moment they’re thrown into conflict and danger, the murderous instinct kicks in. The ghostly servant with its historical baggage comes to the rescue, bringing a ruinous end to both foes and friends.

More on The Constant Companion Tales

- A Request For Betrayal (Paperback: Part Four & Five, Amazon UK, £9.99; Amazon SG, from $20; Waterstones, £9.99; Barnes & Noble, $9.99, and at major bookstores globally)

- The Keeper of My Kin (Paperback: Part One, Two & Three, Amazon UK, £9.99; Amazon SG, from $24; Waterstones, £9.99; Barnes & Noble, $9.99, and at major bookstores globally)

- The series: The Constant Companion Tales (E-book, Amazon Kindle)

- Part One: The Red-Haired Gurkhas (E-book, Amazon Kindle, £2.99)

- Part Two: The Tiger-Man and His Constant Companion (E-book, Amazon Kindle, £2.99)

- Part Three: The Night of the Flying Blades (E-book, Amazon Kindle, £2.99)

- Part Four: The Brotherhood of the Tiger-Men (E-book, Amazon Kindle, £2.99)

- Part Five: A Truce Made In Blood (E-book, Amazon Kindle, £2.99)

- Part Six: The Devil from the Deep (E-book, Amazon Kindle, £2.99)

- Part Seven: Scissors in the Fold (E-book, Amazon Kindle, £2.99)